Satellite images from the 1970s to date show that Lake Chad, which provides economic livelihood to 30 million people, has shrunk by 90%.

There is historical evidence of a Lake Mega Chad, about 1,000 years ago, connected to the Nile, Niger and Zaire rivers with abundant marine life including the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus).

It was up to 600 feet (180m) deep, covering an area of up to 134,000 sq miles (4,000,000 sq km) and drained into the Atlantic Ocean through Benue River and River Niger.

Chad is bounded in the north by Libya, east by Sudan, west by Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon, and to the south by Central African Republic.

Lake Chad has been a major means of livelihood for many in these countries and beyond.

The idea to protect Lake Chad for the mutual benefit of the dependent countries started with Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria and Chad signing (what is now called) the N’Djamena Convention on 22 May, 1964, creating the Lake Chad Basin Commission.

Central African Republic joined in 1996 and Libya in 2008.

Algeria and Sudan made the total number of member-countries eight.

Saving Lake Chad is a common issue to all of them and the Commission reached out to several countries including Italy and China for help.

An Italian firm, Bonifica Spa, proposed digging a 2,600 km (1,625 miles) canal from the Ubanji River (fed by River Congo), through the Chari River in Central African Republic, to re-charge Lake Chad.

This will involve transferring 100 billion cubic metres of water per year from the Congo River in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Instead of using electric pumps, the water table will be lowered in the digging, so that by gravity, it flows from Ubanji (Oubangui) River through a retention dam in Palambo in CAR to the Chari River in Cameroon, to Lake Chad.

In February, 2018, a “Save Lake Chad Conference” co-organised by Lake Chad Basin Commission and UNESCO, was held in Abuja, Nigeria.

The Heads of State of the Lake Chad Basin countries, UNDP, and 1,100 participants in the conference accepted inter-basin water transfer from the Congo basin as the only viable solution to saving the badly shrunk lake.

Kinshasa got concerned with not only the environmental impact of such a huge project, but also on the possibility of losing too much water in the Congo basin.

It is doubtful if their fears were assuaged by assurances of Bonifica Spa that only 4% of the water in the Congo River will be diverted for the project.

Earlier traditional remote sensing data showing a slowly, but steadily shrinking lake, were mostly disregarded.

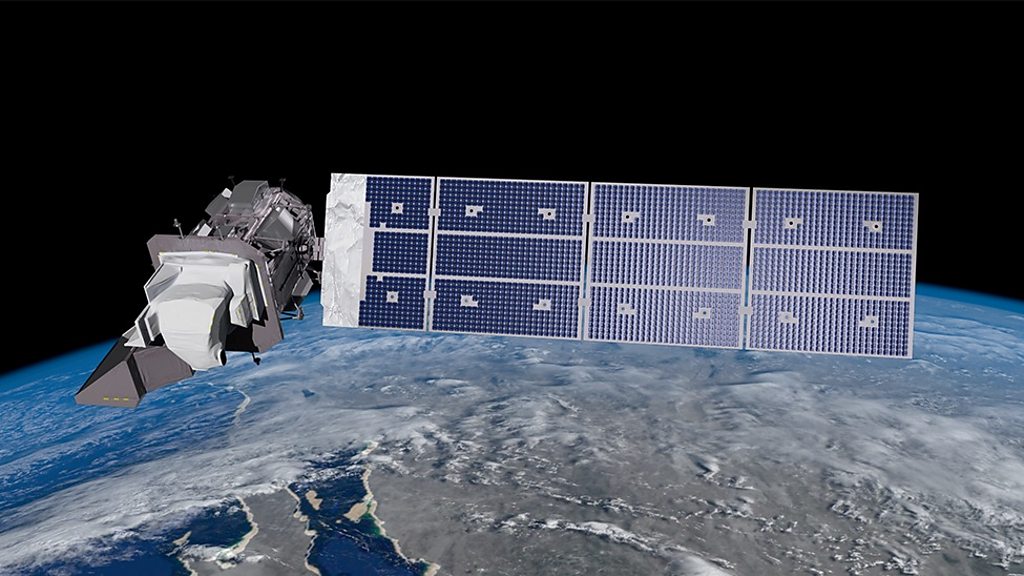

However, free non-stop images from American Landsat 1 from 1972 to 1978, Landsat 2 from 1975 to 1982, Landsat 3 from 1978 to 1983, Landsat 4 from 1982 to 1993, Landsat 5 from 1984 to 2013, Landsat 7 from 1999, Landsat 8 from 2013, and Landsat 9 from 27 September, 2021 showed the true picture of the lake over time.

This helped in re-establishing the Landsat programme as the longest Earth observation mission in the world (Landsat 6 was launched on October 5, 1993 on a Titan II rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, but failed to reach orbit).

Additional images from NigeriaSat-1 from 2003 to 2008, NigeriaSat-2 from 2011, the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-2A satellite from 2015, Sentinel-2B from 2017, among others, were enough to raise serious concern.

Images from other satellites, including ESA’s Envisat satellite, using Medium Resolution Imaging, from 2008 to 2020, even suggest that Lake Chad has shrunk by 95%.

PRESIDENT DEBY’S DEATH: MORE TROUBLE FOR SHRINKING LAKE CHAD

There was deep concern that the death of President Idris Deby of Chad will further jeopardise the efforts to re-charge the shrinking Lake Chad.

His death promoted uncertainty and insecurity as many countries, including the US, asked their diplomatic staff to leave that country.

President Idris Deby was shot as he visited a trouble spot held by rebels in Chad and died soon after.

He had been managing several conflicts which have displaced 2.5 million of his countrymen and the drying Lake Chad is an unwelcome, added problem, if not partly the cause.

Emboldened by the death of President Deby, the rebels threatened to take over the capital, N’Djamena.

The matter at hand then, was not to re-charge Lake Chad, but stopping a Chadian crisis from further de-stabilising the countries in what was left of the Lake Chad basin.

Chad is one of the frontline states in the Lake Chad Basin Commission.

She gained independence from France in 1960 and Idris Deby was President of that country since 1990 till his death on 19 April, 2021.

Chad, by 2018, had a labour force of 7.3 million; 80% of them are in subsistence agriculture. Life expectancy is 48 years in Chad and literacy level is 32%.

All the countries in the Lake Chad basin – Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Central African Republic, Libya, Algeria and Sudan – are developing countries and have similar problems.

President Deby visited President Muhammadu Buhari in Abuja on 27 March, 2021 (barely one month before his death) for discussions on the way forward on the proposed inter-basin water transfer.

The economic hardship brought about by the shrunk lake has reportedly, further worsened the security situation in the basin.

President Deby: “We are neighbours and we have similar problems.”

President Buhari: “It is imperative that there be water transfer to Lake Chad from the Congo Basin so that people can resume their normal lives. Lake Chad is 10% of its original size and 30 million people are adversely affected.”

There is no evidence that Kinshasa has softened its stance and reports of President Deby threatening that the water will be taken by force if Congo still refuses, may not have helped matters.

Money for the project is not the limiting issue as the governments of Italy, France, China and the African Development Bank are all willing to assist.

What is now left seems to be the needed political will and action after satellites, science and technology, have provided the necessary information and solution.

It is in this regard , that the death of President Deby, together with the insecurity in Chad, is a big blow to the efforts in inter-basin water transfer to re-charge Lake Chad.

HOPE RISES FOR THE BASIN

On 14 May, 2021, the late President Deby’s son, Lieutenant-General Mahamat Idris Deby, who succeeded his father, visited President Muhammadu Buhari in Abuja.

He assured Nigeria that as President of a Transitional Military Council, he will return Chad to democracy in 18 months and that he will not run for President in the election.

Deby: “We rely on our brother country, Nigeria, as we have shared history, culture and geography. We are ready to be guided by you in our journey to constitutional rule.”

Buhari: “We are bound together by culture and geography and we will help in all ways we can. Nigeria appreciates the role Chad played in helping us to combat terrorism and we will continue the collaboration.”

Lt. General Deby has reportedly, pushed back the rebels and is stabilising the country.

He survived a constitutional crisis as to whether the Vice President, and not him, should succeed his late father.

On 1 October, 2022, he extended the transition from 18 to 24 months.

On whether he will change his mind and run for President in the coming election, he said he prefers to leave that question to God.

As things turned out, he contested in the controversial election of 6 May, 2024, and was officially declared the winner with 61.3% of the votes.

The opposition called for a nationwide protest and rejected the results as flawed.

The fighting in Sudan (a Lake Chad Basin Commission member-country) between the government and the Rapid Response Forces which started in 2023, with several failed ceasefire agreements, is pushing thousands of refugees into Chad and South Sudan.

Bola Tinubu, who succeeded Muhammadu Bihari as President of Nigeria in 2023, made a campaign promise to recharge Lake Chad, but is busy with many internal economic problems and labour unrest.

The forceful change of government in West African countries like Niger and Mali is creating another problem of distraction and non-cooperation.

By January, 2024, former French colonies under military rule – Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso – withdrew from the joint economic body of West Africa, ECOWAS.

In the 66th Ordinary Session of ECOWAS Heads of State and Government on 15 December, 2024, in Abuja, they were granted a grace period of January 29 to July 29, 2025, to re-assess their decision before their withdrawal takes effect.

The stalemate continues.

pictures courtesy: presidency, landsat, esa, nasrda, un, vanguard